Sometimes the simplest forms of venting make the most sense.

Temperature and humidity – maintaining this balance can be a constant source of struggle for greenhouse producers. As summer time rolls around, sometimes the simplest forms of ventilation can make the most sense in time and expense.

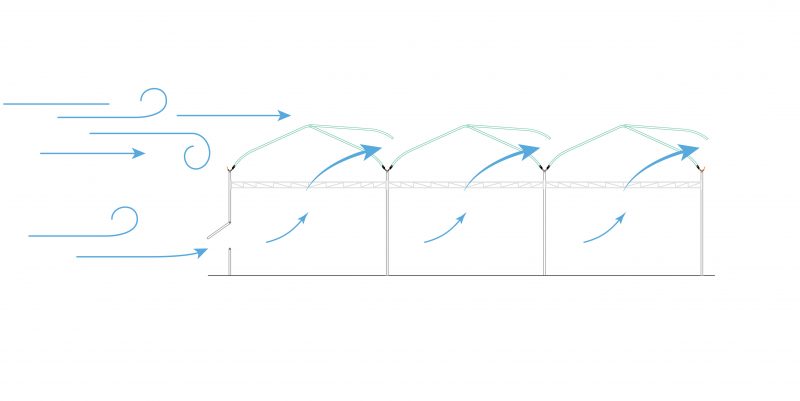

“Natural venting is by far the most popular form of ventilation for modern greenhouse growers in the Northern Hemisphere,” says Leigh Coulter, president of GGS Structures, based in Vineland, Ont. As she explains, natural venting is equally popular for gutter-connected and ground-to-ground freestanding greenhouses, where this type of ventilation can excel. To understand why, Coulter draws a literal picture shown here.

“Roof vents operate on the principal of the chimney effect. Hot air inside the greenhouse rises naturally. By placing a venting on the leeward side, wind travelling over top the vent creates suction pressure that pulls the hot air out of the greenhouse. Vents closer to the ground on the windward side let cooler outside air come in to replace the hot air that is being pulled out.”

Built from taller posts, the height of gutter-connected structures allows for a greater chimney effect. Freestanding greenhouses can make use of both roof vents and rollup sides to increase the amount of natural ventilation. In a correctly designed greenhouse, the results would be even cooling within the crop, for a more uniform product.

That being said, there are situations where natural venting may not be as suitable.

“If you need your greenhouse temperature to be below ambient temperature and you are in a dry climate zone, then fan and pad cooling is better than natural ventilation,” Coulter explains. “But fan and pad do not work as well in humid climates, so natural ventilation is better in those situations.”

Before the summer heat peaks, Coulter recommends checking airflow from vents, having racks greased and conducting a proper maintenance check. “To visualize airflow you can use coloured smoke bombs as a low tech solution to see how the air flows through the greenhouse. This technique can also be used to see where you have air leaks that you may want to eliminate or reduce before winter.”

She emphasizes that ventilation is only one part of environmental control. “Humidity and temperature and light levels also play a roll in determining how the greenhouse systems operate. A good environmental computer will take inputs from both the outside environment and the growing environment and determine what needs to be adjusted to maintain the ideal environment for the crop.”

For those looking to retrofit older greenhouses, Coulter says they’ve been able to add natural venting to many older greenhouses over the years.

“All that is required is for us to know the structural details of the existing greenhouse, the geographic location for climate data, and the crops you are growing. From there we can build a plan with the grower.”

In January’s issue of Greenhouse Canada, readers were introduced to the concept of ‘Growing by Plant Empowerment’ (GPE). Combining grower experience and knowledge of plant physiology, the goal of GPE is to optimize the behaviour of plants in the greenhouse environment by maintaining critical balances involving energy, water, CO2 and assimilates within the plant.

These balances can be monitored by sensors, combined with crop measurements, then interpreted in the context of plant physiology and physics to help finetune and improve the crop.