The Adelaide Plains, often referred to as Australia’s “glasshouse capital,” is home to over 1,000 hectares of greenhouses producing a third of South Australia’s vegetables. This region, with an industry worth over $300 million annually, faces a constant battle against pests and diseases due to the high concentration of protective cropping. As a result, farmers here have increasingly turned to Integrated Pest Management (IPM) — a biological approach that uses beneficial insects, or “good bugs,” to combat harmful pests.

According to Andrew Braham, a local capsicum grower, the close proximity of greenhouse operations means that pest problems can spread rapidly between farms. Conventional pest control, relying on chemical sprays, has led to pesticide resistance, making it harder to maintain crop health. “Bugs are very intelligent creatures,” Braham notes. “They are able to build resistance to chemicals.” This growing challenge prompted him to adopt IPM as a more sustainable, long-term solution, with great success.

IPM involves the introduction of beneficial insects that naturally prey on pests. For example, small but highly effective wasps like Aphidius target and parasitize aphids, one of the most destructive pests in vegetable farming. Dr. Anita Marquart of Biological Services, a company that supplies these beneficial insects, explains how Aphidius works: “The wasp lays its egg inside the aphid, and the larvae consume the aphid from the inside, eventually turning the dead pest into a cocoon where a new wasp hatches.”

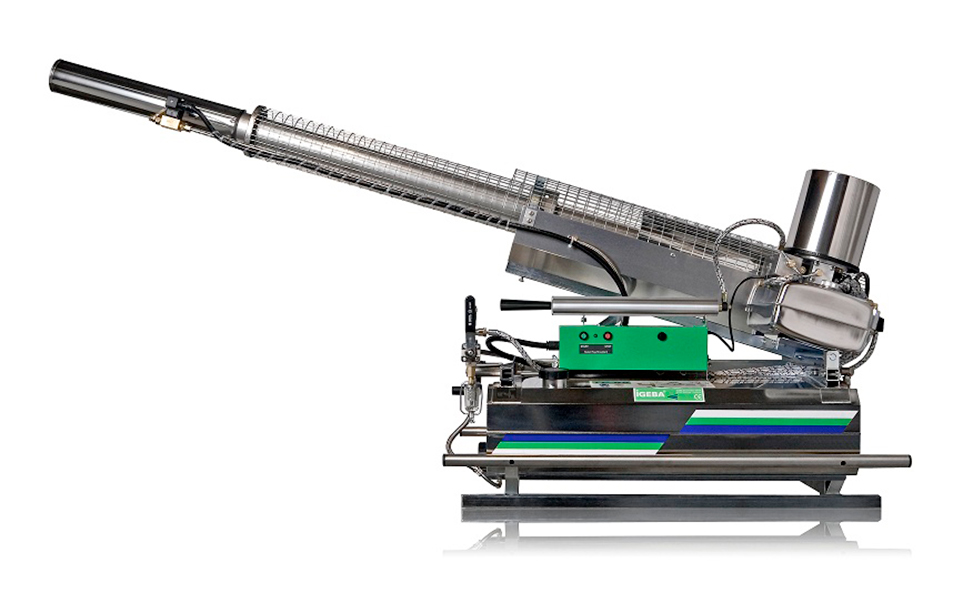

This method is not only effective but continuous. Once introduced into the greenhouse, these beneficial bugs work around the clock without the need for re-application, making it a low-maintenance and cost-effective pest control option. Andrew Potter, who has been working in Virginia’s greenhouse industry for over two decades, describes IPM as an “army of bugs” that constantly patrols crops, reducing the need for human intervention and eliminating disruptions caused by pesticide application.

The benefits of IPM go beyond pest control. Healthier crops, free from pesticide residues, appeal to increasingly health-conscious consumers. Moreover, IPM contributes to environmental sustainability by reducing the chemical load on the land and nearby ecosystems. With pest resistance to chemicals rising globally, Braham and other growers in the Adelaide Plains believe that IPM is essential for the future of farming.

A look at Europe provides insight into what may lie ahead for Australia. In Spain, for instance, regulations have been introduced that require the use of IPM if growers want to export produce to European Union markets. The shift away from chemicals has not only succeeded in pest control but also opened up international markets. Braham believes Australia must adopt a similar approach if it hopes to maintain sustainable vegetable production and combat exotic threats, such as the recent outbreak of tomato brown rugose fruit virus, which has severely impacted local businesses.

While beneficial bugs do not directly control viral diseases like this, IPM has helped growers manage pest populations that can weaken crops and make them more susceptible to other diseases. As pest challenges continue to rise, collective adoption of IPM across the region will be crucial in maintaining the health and productivity of South Australia’s vital vegetable industry.

The adoption of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) in Australia’s greenhouse capital offers a promising solution to the growing problem of pesticide resistance and pest outbreaks. By using beneficial insects to control pests, farmers can reduce chemical use, improve crop health, and support sustainable farming. With global examples of successful IPM adoption, it’s clear that biological pest control is the future of agriculture, ensuring cleaner, healthier food for consumers and a more resilient farming industry.